It’s all a bit woolly

The first problem with pinning down who I really am is that no one even knows my name. No one knows what to call me. Even me. On first meeting people always say, ‘Do we call you Ade or Adrian?’ and I usually reply, ‘Whatever you can manage’, because in truth I can’t stomach either.

How did this come to pass?

I arrive into this world ‘quite quickly’ at the bottom of the stairs in a modest, pebble-dashed semi in an area of Bradford called Wrose. It’s now BD2, but I’m born two years before postcodes were invented – which is probably why the ambulance can’t find us, and why my dad ends up delivering me.

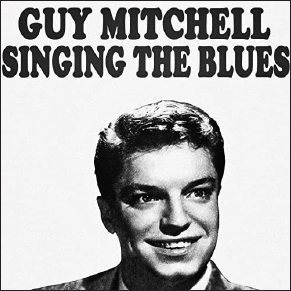

This happens on 24 January 1957 when Guy Mitchell is toppermost of the poppermost with ‘Singing the Blues’.

This isn’t a conscious memory of course, and Guy isn’t at the birth, even though his face suggests otherwise. Is that joy? Or horror? Or a clever mix of the two? One disguising the other? Everything’s fine. This is normal. I still love you. Aggghh! The horror! The horror! Hide it for ever! Never speak of it!

It could be the very same expression on Dad’s face, because he has no training, no aptitude and apparently no stomach for it, but it’s an emergency and he’s the only one there, apart from my mum, obviously. And I survive.

The wool rug at the bottom of the stairs doesn’t.

My family history is very woolly. It’s precise, but it’s precisely about wool.

At the time I arrive Bradford is struggling with a decline in fortunes. My earliest memories of the city are of all the buildings being jet black – a thick residue of filth and soot that had built up from all the coke and coal that was burned to keep the machines going in the mills.

Back in 1841 two-thirds of the UK’s wool production was processed in Bradford, and the population doubled in a decade. By 1900 there were 350 mills – scouring, carding, gilling, combing, drafting, spinning and twisting to produce yarn and fabric. It was boom time, and despite the amount of muck and grime being chucked out by all those chimneys there was a lot of civic pride in all that industry. To compete with the town halls of neighbouring Leeds and Halifax, Bradford built a town hall with a clock tower based on the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence, and boasted of the city being built on seven hills – ‘just like Rome’.

While Manchester was nicknamed ‘Cottonopolis’, Bradford became ‘the Wool Capital of the World’. Not quite as snazzy, but no less true. Worsted – a superior yarn made using only the longest fibres, very popular for making suits – became a speciality of the city and some people tried to adopt the name ‘Worstedopolis’, which sounds like a bad review for a Greek restaurant on TripAdvisor, and thankfully it didn’t catch on.

This constant desire to make a name for itself, to be better than Leeds and Halifax, to be on a par with Manchester, or even Florence and Rome, has the whiff of an inferiority complex. Can a city have a collective consciousness? All my immediate forebears were born in Bradford, and while I don’t think they felt inferior exactly, they certainly seemed to ‘know their place’. I was brought up to think that other people probably knew better than me. I’ve always struggled with the idea that I’m not good enough.

My mum is called Dorothy and her maiden name is Sturgeon, a name that comes originally from Suffolk, which was once a great sheep-rearing county. It seems the Sturgeons must have followed the sheep to Bradford because they ended up in the Wool Capital of the World by the middle of the nineteenth century.

Her dad, George Sturgeon, worked on the shop floor of the dark satanic mills and died of a heart attack three years short of his retirement, and a year before I was born.

Her mum was Doris (Grandma Sturgeon), though her maiden name was Luscombe – a name that comes originally from Devon, where I now live in a bizarre case of reverse migration. There were, and still are, a lot of sheep in Devon – I’ve raised a few myself – but the Luscombes too followed the sheep, and the work, to Bradford. Doris worked in a weaving mill until she got married when she was apparently sacked for . . . getting married. She took up moaning as a full-time occupation. And cheating at canasta with a young boy, namely me. If she were alive today I could happily tell her that you don’t have to shout ‘I’m in Meredith’ when you produce your first meld, that putting the first red three on the table doesn’t entitle you to all the red threes as they appear, and that you can’t play the game with just two people anyway.

My dad was Fred Edmondson. That was his full name. Not Frederick, not Alfred, not Manfred. And no middle name. No nonsense. Just Fred. He’s one of the very few of my extended family not to be born in Bradford. Oh yes – this is the fruity part of the plot – he was a foreigner, born in Liversedge, a full seven and a half miles from the centre of Bradford. Virtually . . . Dewsbury.

Dad’s dad was Redvers Edmondson (Grandad Ed) – named after the great general of the Zulu and Boer Wars, and heroic winner of the Victoria Cross, Redvers Buller. Grandad was a market trader. And no, he didn’t wear a pinstripe suit and a bowler hat and gamble with people’s pensions, he worked in actual markets, with his hands, on actual market stalls, selling, you’ve guessed it, wool.

He was married to Ruth (Grandma Ed), who died in the summer of 1977 when ‘I Feel Love’ by Donna Summer was top of the charts. Nothing could be less like Grandma Ed than ‘I Feel Love’. I never hear her say anything nice about anyone. She is dismissive of everyone and everything. In the 1960s Billy Smart’s Circus is on the telly every Easter. We’ll sit there watching some trapeze artist shoot through a hoop of fire and land on an elephant’s back, all whilst juggling actual lions, and Grandma Ed (a short dumpy woman with thick ankles – she looks like the grandma in the Giles cartoons) will say: ‘Oh, I could do that with a bit of practice.’

They’re very big in the church, Grandma and Grandad Ed. Which might explain the lack of love and compassion. Except it isn’t the church, it’s the mission. The Sunbridge Road Mission. I haven’t set foot in it since the late sixties but at that time it was an evangelical Methodist enclave that, if it were in another country, might be called fundamentalist.

The Bible is everything. It’s God’s word or nothing. Except the rude bits, obviously. Not the bit in Genesis when Lot’s daughters get him drunk and have sex with him; or the bit in Deuteronomy about not being allowed to go to church if you’ve damaged your testicles; or the bit in Judges when a woman gets gang raped, dies, and is cut into twelve pieces which are sent to the twelve tribes of Israel. Mention them and you’re in trouble. And it’s surprisingly easy to get into trouble when this stern Methodist God is watching you.

One Sunday, Grandad, who’s one of the ‘elders’, gets me and my cousin Kevin out in the corridor for some misdemeanour – perhaps we’ve been smiling – and bangs our heads together so hard that half of Kevin’s front tooth breaks off and lodges itself in my forehead. I can still feel the dent. Kevin has a lifetime of dental problems. Praise the Lord.

It’s a tough religion to go with the tough life of working in a tough industry in a tough city in tough times. And it’s all in decline!

Even Dad’s faith is in decline. When I get to the age of seven Dad stops going to the Mission.

‘Hurrah,’ I think, ‘that’s surely the end of it for me, as well? No more sitting in that fusty room with the other bored kids taking it in turn to read the Bible aloud.’

But no. Every Sunday my sister and I are now picked up by Grandma and Grandad Ed and are dragged along – on our own – to have all the joy sucked out of us. Our parents and our two younger brothers are allowed to stay at home and hang on to their joy. Despite asking for an explanation for this over the years none has ever been forthcoming.

It must have been a moment of high rebellion on Dad’s part, and I’m rather proud of him – though it seems odd he then couldn’t accept the rebellious streak in me further on down the line. His mum was the sternest woman I ever knew, and standing up to her must have taken some bottle. Although there was obviously some form of negotiation which must have gone along the lines of:

Grandma Ed: There is only one true path to salvation.

Fred: I can no longer see the path, Mother.

Grandma Ed: Then you are lost to me but I will take your first- and second-born children, that they may become truly miserable, like me.

Grandma Ed must be aware that there’s a world beyond the Mission because she’s a cousin of Thora Hird, the famous actress – one of Alan Bennett’s muses.

Well that’s where you got the acting bug from then – it’s in the blood!

But no, we never see Thora or any of that side of the family. Partly because they’re from Lancashire, anathema to Yorkshire folk, but mostly because of Thora’s decision to become an actress. The Bible bashers on our side of the Pennines think it’s tantamount to becoming a prostitute. There’s a rift. They don’t speak. Neither do they turn the other cheek. Or love their neighbour as they love themselves.

‘Ooooh, I feel love, I feel love, I feel love, I feel love, I feeeeeel love.’

Although Thora very definitely wins the argument in my view. First by appearing in the TV show Hallelujah!, a sitcom about the Salvation Army, set in the fictional town of Brigthorpe which looks suspiciously like Bradford, and which incidentally features the fantastic Patsy Rowlands, who goes on to play Mrs Potato, Spudgun’s mum in Bottom.

And second by going on to present Songs of Praise and beating them at their own game.

I eventually meet Thora at some awards do in the nineties, mention our family connection, and she gives me the oddest look before simply saying, ‘Oh.’

But back to the wool industry before it dies out completely.

How does this relate to your name? You were right about tangents.

It’s coming, I promise you.

Uncle Douglas also works on the markets, driving out before the crack of dawn to set up his stall in South Elmsall, Scunthorpe or Doncaster. He’s also – well guessed again – selling wool. I sometimes go with him and help set up the stall, but my main job is to wander around the market and keep a steady eye on how much his rivals are selling for, so that he can adjust his prices accordingly. There’s a bloke on a neighbouring stall selling crockery, he’s brilliant at the patter and can display an entire dinner service along one outstretched arm. I want to push him over at the moment of greatest peril but never summon up the nerve.

And Uncle Colin, well he’s a step up – he works for a wool-importing business. He goes around the world, looking at sheep. When he comes back he has a slide show and we all go round to his house and look at the sheep he’s looked at. Please don’t judge us too harshly – remember, we’d only recently gone from two to three channels on the telly.

But of course there isn’t room for everyone in the wool business, especially as it’s in steep decline. So rather like those aristocratic families where the eldest inherits, the next becomes a priest, the third a soldier and so on, my family diversifies. Dad becomes a teacher, my uncle Tom becomes a missionary in the Cameroons (I’m not making this up), and my uncle David becomes an air traffic controller at Yeadon airport. Now called Leeds-Bradford airport. Because it’s neither in Leeds nor Bradford. It’s in Yeadon.

But they all do time on the wool stalls at some point in their lives.

So the bulk of my family history is tied to wool and wool production in a grimy, industrial, northern town; they don’t mind getting their hands dirty, they get stuck in, and they have no-nonsense names to match – Fred, Douglas, George, Colin – unless they happen to be named after a Victoria Cross winner, like Redvers. And amidst all that northernness, grit, and war heroics, my parents decide to give me a girl’s name: Adrian.

I told you we’d get there!